Tatouage maori : histoire et origines d'un art polynésien ancestral

13/12/2024

Les origines du tatouage Māori

Découvrez un art ancestral qui transcende le simple ornement : le tatouage maori, fusion de spiritualité, d'histoire et de culture, incarne bien plus qu'un motif sur la peau – il raconte une vie, un héritage, et une identité profondément enracinée dans la tradition polynésienne.

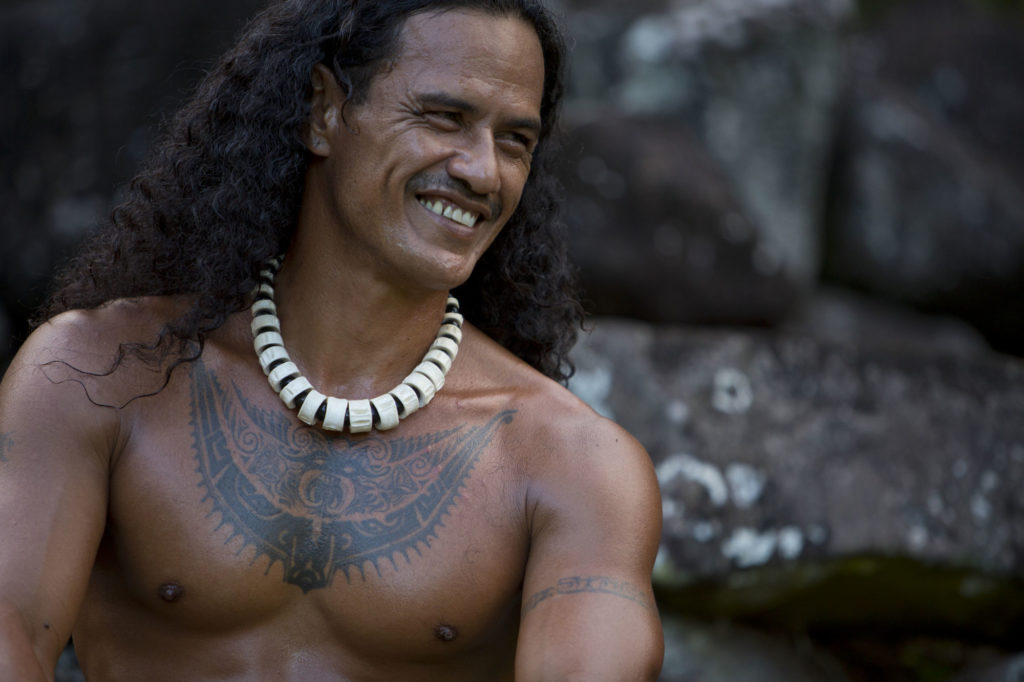

©Tahiti Tourisme

Tatouage tribal, le tatouage Maori est issu de la tribu polynésienne Maori, habitants de la Nouvelle-Zélande.

Le mot "tatoo" ou "tatouage" est dérivé du mot tahitien Tatau, qui signifie "marquer" ou "frapper". Ses origines précises sont inconnues, mais on trouve des tatouages Māori dans tout le triangle polynésien, avec des exemples allant des îles Cook et de la Polynésie française (à l'exception de nombreuses îles au sud des Australes et à l'est de Tuamotu) à Hawaï, Samoa, l'île de Pâques et la Nouvelle-Zélande.

En marquisien, langue distincte du tahitien, un tatouage polynésien est décrit comme "E Patu Tiki", ce qui signifie "pour frapper une image", et est reconnu comme le lieu où les motifs les plus poussés et les plus décoratifs ont été découverts.

Selon les origines de l'art du tatouage Māori, ils étaient considérés non seulement comme une décoration, mais aussi comme un langage, un symbole de pouvoir et une distinction honorifique dans la société polynésienne traditionnelle. Ils avaient également une importance sacrée, car on pensait qu'ils possédaient des capacités magiques héritées de Dieu. Les Polynésiens utilisaient donc les tatouages pour se distinguer, affichant leur statut social, leur rang, leur origine géographique, leur histoire familiale, leur courage et leur pouvoir. Toutes ces informations étaient gravées sur le visage (un moko) et le corps et constituaient une sorte de carte d'identité pour chaque personne.

Un tatouage pouvait également marquer l'accomplissement de rituels sociaux importants tels que le passage de l'enfance à la puberté, le mariage, etc. En outre, une image peut représenter des événements remarquables de la vie de la personne concernée, comme des actes de bravoure à la guerre, des prouesses en tant que chasseur ou pêcheur, ou simplement un élément décoratif sur la peau.

Les types de tatouages Māori

©Tahiti Tourisme

Il y avait trois types de tatouages tribaux : ceux des dieux, des prêtres et des princes, qui étaient héréditaires et donc réservés à leurs descendants ; ceux réservés aux chefs masculins et féminins ; et le troisième type qui était réservé aux chefs de guerre, aux guerriers, aux danseurs et aux rameurs.

Certains de ces motifs étaient destinés à empêcher les individus de perdre leur mana - la puissance divine responsable de la santé, de l'équilibre et de la reproduction, ainsi qu'à combattre les forces maléfiques. Dans la culture des îles Marquises, les tatouages n'étaient pas seulement un privilège, mais aussi une obligation. Ils constituaient un lien avec la mémoire sacrée des ancêtres et avaient un impact considérable sur la vie des gens. Et parce qu'elle était indélébile, l'œuvre témoignait de leurs origines, de leur rang et de leur bravoure lorsqu'ils étaient appelés à se présenter devant leurs ancêtres, les dieux du pays légendaire de "Hawaiki", dans l'au-delà.

En 1819, le tatouage polynésien a été interdit dans toutes les îles avec l'introduction du code Pomare, lorsque les missionnaires ont converti le roi au catholicisme et une grande partie de sa tradition a été perdue. Elle a connu un renouveau dans les années 1980 et, si les pressions religieuses ont disparu, la force symbolique plus fondamentale est restée : imprimer de façon permanente une histoire, un souvenir ou un événement sur la peau.

Les tatouages polynésiens sont plus que jamais un moyen d'affirmer son identité et de démontrer son attachement à la culture polynésienne. Les tatoueurs développent leur art pour reproduire des motifs traditionnels, des motifs décoratifs (comme les dauphins ou les raies manta) et, plus récemment, pour créer des motifs totalement nouveaux mais directement inspirés de la tradition.

Comment un tatouage Māori était créé

Dans les îles de la Société, les tatoueurs étaient connus sous le nom de "tahua'a tatau", tandis qu'aux Marquises, ils étaient appelés tuhuka (ou tuhuna) patu tiki. Leur mission était de laisser une impression indélébile sur chaque membre de la communauté à chaque étape de sa vie.

Les artistes devaient être capables de transmettre leur savoir avec une remarquable habileté car leur métier se transmettait fréquemment de père en fils.

Les techniques du tatouage Māori

©Stephane-Mailion - Tahiti Tourisme

Des peignes pointus en os, en nacre ou en écaille de tortue, fixés à un manche en bois, étaient utilisés conjointement avec un maillet. Les dents du peigne étaient trempées dans une encre à base de charbon de noix de bancoulier (Aleurites Moluccana), diluée dans de l'huile ou de l'eau. Le nombre de dents du peigne était déterminé par la quantité de surface à couvrir.

Il pouvait y avoir de 2 à 12 dents, mais certaines personnes affirment en avoir vu jusqu'à 36. L'artiste utilisait un bâton de charbon pour créer le dessin sur le corps avant d'appliquer son encre et la cérémonie de tatouage devenait un rituel solennel exécuté au rythme des tambours, des flûtes et des cornes de conque.

Pour certaines familles, la cérémonie était coûteuse : cochons, maillets de guerre, tapa (tissu d'écorce peint) et tout ce que la famille possédait étaient utilisés pour payer le tuhuka. Par conséquent, de nombreuses personnes en bas de l'échelle sociale ne pouvaient pas se permettre de nombreux tatouages.

Symboles de tatouage polynésien

Aux îles Marquises, les corps et les visages pouvaient être complètement couverts de tatouages, ce qui les distingue de ceux à Tahiti et dans les îles Sous-le-Vent où il semble que le visage n'ait jamais été tatoué.

Selon la coutume, les hommes portent généralement des tatouages polynésiens du haut des genoux jusqu'au bas du dos, tandis que les femmes portent généralement des tatouages sur les mains. L'emplacement du tatouage dépend également de la famille et de la profession de la personne. Une masseuse, par exemple, peut se faire tatouer les mains ou un professeur se fera tatouer le visage, également appelé moko, sur la lèvre inférieure. Les motifs populaires sur les bras, les jambes et les épaules étaient des motifs abstraits et géométriques sous forme de cercles, de croix et de rectangles, ainsi que des plantes et des animaux figuratifs.

Chaque symbole a une signification, dont voici quelques exemples :

Enata

Les figures humaines, appelées "enata" en marquisien, étaient utilisées pour représenter des personnes ou des parents dans le tatouage. Le symbole peut représenter un homme ou une femme, ou une figure divine, et il a des significations qui sont liées à l'humanité et aux relations. Lorsque l'enata forme un motif, il ressemble à un groupe de personnes se tenant la main. Une rangée d'enata en demi-cercle représente souvent le ciel et les ancêtres qui gardent leurs parents vivants. Si les enata étaient retournés à l'envers, ils pourraient représenter des ennemis vaincus.

Les dents de requin

Les dents de requin sont extrêmement pointues et se caractérisent par des triangles. Elles représentent la bravoure et l'héroïsme. Dans de nombreuses cultures, elles représentent une variété de choses telles que l'abri, le leadership et la vitalité, ainsi que des traits de caractère tels que la brutalité et la flexibilité.

Un fer de lance

Le fer de lance est un ancien symbole de guerre, de bataille, d'inimitié et de victoire utilisé pour représenter le guerrier qui est en vous. C'était un symbole populaire dans la classe des guerriers de la tribu, où une flèche pointant dans la même direction indiquait la victoire sur l'adversaire. On dit aussi qu'elle représente la protection, l'endurance et même la piqûre d'un animal.

L’océan

Les océans sont souvent considérés comme un lien entre le monde visible et le monde invisible, représentant le flux et le reflux de la vie et de la mort, et ont une influence importante dans divers mythes et cultures. L'océan est une seconde maison pour les Polynésiens et, comme dans de nombreuses cultures, c'est un lieu de repos dans l'au-delà, le symbole des vagues étant utilisé pour représenter l'océan.

Les tikis

Le tiki (le premier humain à devenir un ancêtre vénéré) a été une influence essentielle dans le style marquisien, représentant un être mi-humain, mi-dieu qui est l'ancêtre des humains. Il véhicule la force et la masculinité et sert également de porte-bonheur, protégeant son porteur des dangers et des mauvais esprits. Le tiki peut également représenter des ancêtres, des prêtres et des chefs déifiés qui sont devenus des demi-dieux après leur mort. Ils représentent la protection, la fertilité et servent de gardiens.

Une tortue

La tortue est un symbole bien connu des tatouages polynésiens et le symbole le plus important de l'unité de la tribu et de la famille. Dans la vie, elle représente l'immortalité et le calme et est une créature importante dans la culture polynésienne, où elle est associée à la virilité, la vitalité, l'endurance et la force.

Un lézard

Les lézards ont un large éventail de connotations et de significations dans la culture polynésienne. Ils sont connus pour leur résistance face à l'adversité, et représentent donc une force qui protège l'homme et la femme du mal et d'autres présages. Les hommes invoquent fréquemment des dieux (atua) sous la forme de lézards et de geckos pour servir de moyen de communication entre les dieux et les hommes. Ils apportent la bonne fortune, ont accès au monde spirituel et ont le pouvoir de détruire.

Le dauphin

Le tatouage dauphin, comme le tatouage raie, représente la liberté. Dans la mythologie polynésienne, le dauphin a guidé les Māori vers la terre promise tout en les protégeant des requins. C'est un animal important pour les Polynésiens car il représente la protection et l'orientation.

Aujourd'hui, on trouve des tatoueurs Māori sur presque toutes les grandes îles habitées de Polynésie française. Les visiteurs viennent du monde entier en raison de leur renommée et de la beauté du tatau polynésien. On peut également trouver des tatoueurs polynésiens dans de nombreuses grandes villes du monde, car les tatouages polynésiens ont acquis une reconnaissance mondiale pour leurs racines traditionnelles et leur attrait ethnique authentique.

Eddy Tata, artiste tatoueur à bord de l'Aranui 5

©Tahiti Tourisme-Grégoire-le-bacon

L'Aranui 5 est le seul navire à passagers au monde à disposer d'un tatoueur polynésien traditionnel à bord. Eddy Tata, qui est né sur l'île marquisienne d'Ua Pou, a rejoint le navire en juillet 2016 et a commencé par tatouer l'équipage. Il est désormais le tatoueur résident du navire.

Il a appris à dessiner en regardant son oncle, Moana Kohumoetini, créer des tatouages, et à l'âge de 17 ans, il a commencé à produire ses propres tatouages. À l'âge de 30 ans, il a suivi la formation nécessaire pour devenir tatoueur sur d'autres personnes et il est maintenant un tatoueur polynésien connu et très recherché. Dans son studio à bord, Eddy crée des symboles et des figures anciennes pour les passagers.

Il considère son service comme un moyen pour les voyageurs de se souvenir de leur séjour en Polynésie française, ainsi que comme un moyen pour lui d'utiliser ses talents pour entrer en contact avec des personnes du monde entier.

Tata rencontre les passagers de la croisière pour décider du design de leurs tatouages. Ceux-ci sont basés sur leurs histoires de vie personnelles, leurs expériences et leurs émotions. Si les symboles utilisés peuvent être les mêmes, c'est leur combinaison qui raconte une histoire unique. Eddy tatoue 15 personnes par semaine et environ 700 personnes par an entre ses clients privés à terre et les passagers à bord.

Si vous souhaitez obtenir plus d'informations, n'hésitez pas à visiter ce site qui donne pas mal d'infos sur les tatouages maoris.

Vous souhaitez souhaitez découvrir la Polynésie ? Consultez nos croisières en Polynésie française :

- Croisière Bora Bora

- Croisière Tahiti

- Croisières îles Marquises

- Croisière îles Australes

- Croisière îles Cook

- Croisière îles Pitcairn

- Croisière îles Société

- Croisière îles Tuamotu

- Croisière îles Gambier

À lire aussi